Latitude Living: Clara Calatayud

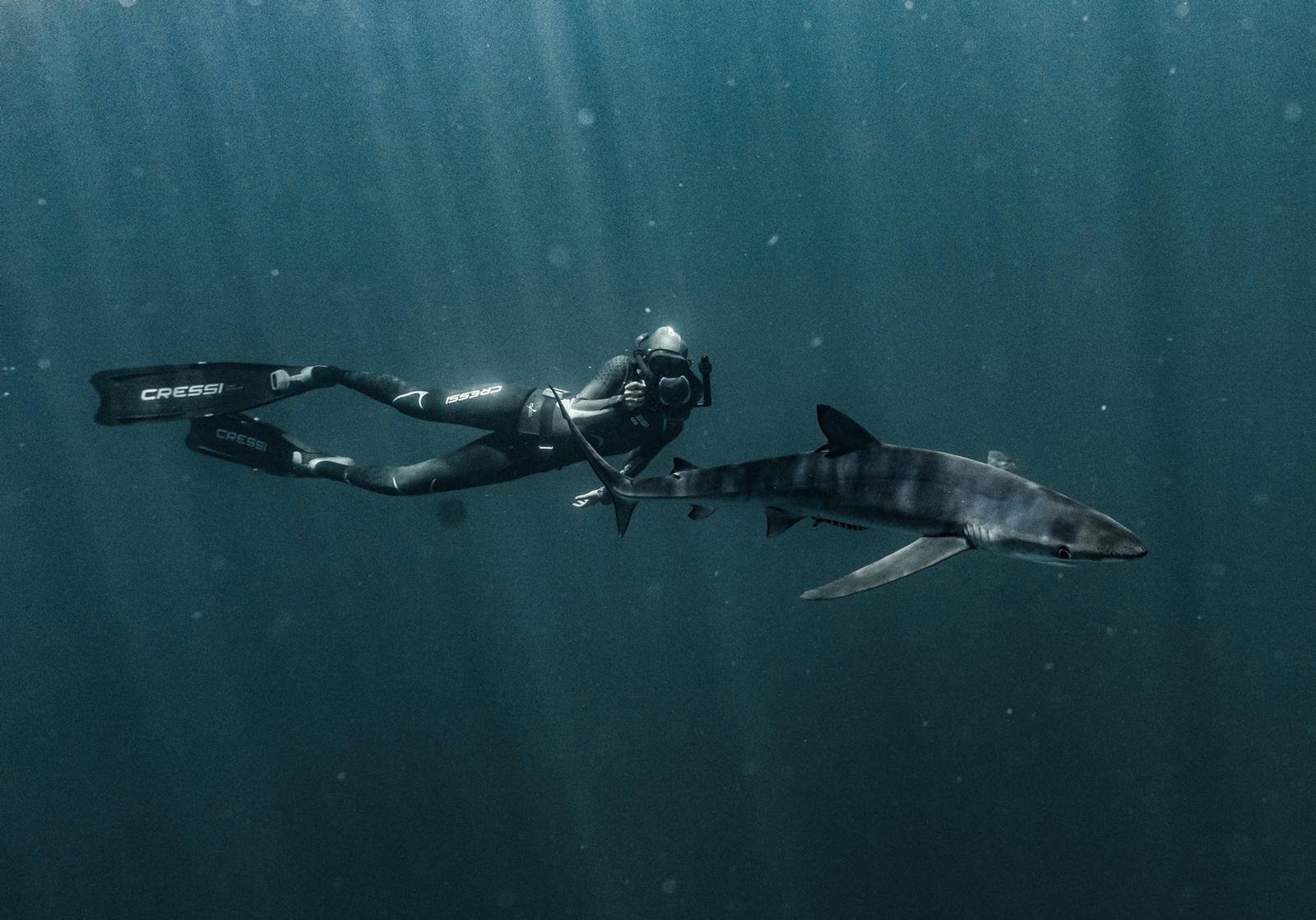

We had the chance to talk with Clara Calatayud - marine biologist and director of Mexico Azul Foundation - and the research and conservation efforts towards sharks in the region. From the definition of pelagic shark to satellite tags, the controversial chumming practices, and the most memorable ocean experience - Clara answers all our questions!

Tell us a bit about yourself, what do you do for a living?

I am Clara Calatayud Pavía, I am a marine biologist and current director of the marine research and conservation programs in Mexico Azul Foundation. I have developed the Pelagic Shark Monitoring Program in Cabo San Lucas since 2016 and I also organize scientific tourism expeditions with local operators here in Baja, following my previous project, The Shark Odyssey, were citizens become shark surveyors and data collectors for some days. I do independent consulting and collaborations for citizen science and pelagic shark monitoring protocols in Spain. Recently, I have been working with blue sharks in the Mediterranean Sea and after some years here in Cabo, I am willing to start tagging shortfin mako sharks soon.

What is Mexico Azul?

México Azul was funded in 2010 as a non-profit Mexican association dedicated to the conservation of habitats and marine species. We seek the union and alliance with different entities to impact public policies, promote awareness through education and generate relevant scientific information, which help us achieve a change in the reality of our seas and oceans. México Azul's mission is to preserve habitats and threatened marine species in Mexican waters, through research, citizen science, and education. We focus on the protection of sharks, marine megafauna, and cooperation with fishing communities for a more conscious use of marine resources.

Explain to us a little about your current and future research here in Cabo San Lucas.

I have been working in Cabo San Lucas since 2016 when I first noticed that shark tourism was flourishing but there was no scientific baseline data on the pelagic shark species visiting the area. I decided to start the Pelagic Shark Monitoring Program, partnering up with shark tour operators that helped collect data on pelagic sharks during their recreational encounters. Citizen science and tourism became essential tools for monitoring these species of sharks that are pretty elusive and fisheries-based information is the main and almost only source of available data to study them. We are currently working to publish the first scientific paper on the pelagic shark monitoring records, from 2016, 2017, and 2018. In this first publication, we explain how environmental factors affect the presence of 4 pelagic shark species and their seasonality in Cabo San Lucas. These species are the shortfin mako shark, the blue shark, the smooth hammerhead shark, and the silky shark. This year we are implementing a digital datasheet to facilitate data entry and thus, expand the participation of more shark tour operators in data collection. Our next goal is tagging shortfin mako sharks from Los Cabos to understand more about their migration patterns and the population dynamics in Cabo San Lucas coast.

What does pelagic mean and how are pelagic sharks adapted to their environment?

Pelagic sharks are active free-swimming shark species that live in the water column and are not closely associated with the sea bottom. In marine ecosystems, the pelagic domain is made up of organisms that live in suspension (plankton) or actively move (nekton) in the water, while the benthic domain is made up of others that live on the bottom (benthos). Pelagic sharks include both “oceanic” and “semipelagic” species: oceanic species spend most of their time in ocean basins away from shore, but they regularly visit continental and insular shelves for feeding and breeding aggregations; semipelagic species can be found in the open ocean but are more related to continental areas over continental slopes and rises.

Pelagic fish have adaptations to the environment they live in, the water column. These adaptations have a lot to do with the need for sharks to swim continuously to compensate for their negative buoyancy (remember sharks, unlike bony fish, do not have a swimming bladder). Sharks are constantly advancing (swimming) to generate hydrodynamic drive and ventilate their gills. To swim continuously, pelagic species have adaptations to reduce friction with water, for example, their fusiform and elongated bodies, presence of precaudal keels to minimize water resistance, more symmetrical caudal fins to create wave thrust. They also have long pectoral fins for their buoyancy and large caudal fin to minimize body roll when swimming.

Some species like the shortfin mako show even more amazing physiological adaptations, like a kind of body temperature regulation, which allows the shortfin mako to maintain a higher body temperature than the water surrounding it. This endothermic system, allows the mako shark to be the fastest shark in the ocean.

What questions do you hope to answer with the satellite tagging research?

One of the most emblematic pelagic shark species that we can observe from Cabo San Lucas is the shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). This species is critically endangered and it has been included in CITES appendix II since 2019 by the proposal of Mexican authorities. The Mexican Pacific could be the last healthy shortfin mako shark population stock and therefore, we need better understanding of the species dynamics to establish proper management measures. Satellite telemetry would help us answer questions like, are these mako sharks coming every year to Cabo or we are seeing different individuals year by year? Do they stay longer near Baja California Peninsula waters, or they leave Baja waters just after their pick season ends in Cabo? Are these sharks moving towards the Gulf of California or to the open waters of the Pacific Ocean? Are mako sharks being fished during the national shark fishing band in Mexico?

What threats do pelagic sharks face and why are they so threatened with extinction?

There are several factors that make the conservation of pelagic sharks quite difficult to achieve. First of all, from the biological point of view, most pelagic shark species present low reproductive potential due to slow growth and delayed maturation; long reproductive cycles; low fecundity; and long life spans, making it very difficult for them to keep up with the fishing pressure. These sharks are also wide ranged distributed and therefore, international agreements are needed to guarantee efficient protective measures. Overfishing may be the main threat to pelagic sharks, tens of millions of individuals are caught each year by high-seas fisheries, either as bycatch or as target species. This level of exploitation is especially problematic because the harvest of oceanic sharks remains mostly unregulated and for the majority of shark species, no international harvest limits have been imposed.

Why is shark research important in Mexico?

In Mexico, there are 113 species of sharks registered and only 3 of them are protected by the national endangered species list (the great white shark, the whale shark, and the basking shark). Mexico has a long and important fishing culture, and there are several legal shark fishing fleets especially in the Mexican Pacific and Gulf of California, depending on the population status of these sharks. Nowadays, several shark fishing communities have noticed a decrease in their captures and claim a lack of resource to maintain their families. Moreover, Baja Peninsula is becoming a popular marine megafauna destination, where sharks are playing an essential role as emblematic, charismatic species attracting thousands of visitors looking for a natural encounter with these pelagic shark species. The majority of information on these species is often obtained by fisheries data, which can be misleading, lacking or inaccurate, that is why is it important to gather data from other sources that help put all the pieces together.

What inspired you to study sharks?

Born in Barcelona I did a lot of research in the Mediterranean, where we have very few sharks left, unfortunately. I had never seen a shark before, even after finishing my biology degree, so I thought about shark research as an impossible dream. Moreover, sharks are often seen as mean animals, aggressive or not very kind, but at the end of the day they are shy and real survivors, I kind of feel identified with them, we are all misunderstood creatures after all.

Can you explain your views on chumming and shark provisioning?

A previous question was to define pelagic shark species and this is important when talking about attraction methods. I believe that when working with highly mobile and elusive species

This is one of the most controversial points for biologists who use attraction methods to study sharks. It has been speculated that the use of food to attract sharks for touristic activities may be changing the behavior patterns of these sharks. Although it must be recognized that there are behavioral changes in some situations where these attraction methods are used, in the case of pelagic sharks and the environment we have in Cabo, it is highly unlikely that we can generate changes in their population dynamics. In order to actually modify sharks’ behavior because of the use of provisioning methods, we should be interacting with the same individuals, at the same point, at the same time, day by day, and repeatedly every year. Given our fieldwork conditions here in Los Cabos, these factors cannot be repeated, therefore there is no constant repetition that makes sharks “learn” how to get food easily. In fact, since I started monitoring sharks during these tour operations, I have not yet noticed a decrease in the arrival time of the sharks at the bait, they do not arrive sooner than in previous years.

What would you most like to change in the world today?

I would like to change the whole system! I feel human beings have become absurd and individualistic species. We forgot we are gregarious and intelligent animals, apparently, the only “intelligent consciousness” of our planet, and our species’ mission should be using our capacities for the common good (and when I say common I refer to all alive organisms, not just the human population community). I would like to eliminate those factors that make human beings not pure animals anymore: ego, money, religion, and technology. Maybe when we delete them, we will be back on track for our species’ mission on Earth. But at the end of the day, what I would like to change the most in the world today would be my ability to adapt to the continuously changing scenario in our lives. Adapt or perish…

What is your most memorable ocean experience?

One of the first sharks I saw I did not even know it was a shark it even touched me and honestly, I freaked out! I was living in the Seychelles islands (2006 and 2007) for a sea turtle project. One night I was doing the night patrol for nesting females on a beach that could only be reached by sea, walking on some shallow reefs. That night, I was carrying my fieldwork materials in a backpack I placed on the top of my head to cross the water and don’t get wet. I had a torch in my mouth so I could see my way through the reef, and that is when I felt a gritty feeling in one of my calf’s, I could tell it was not a regular fish…. I put the torch down and I saw a shark between my legs!!!! I started running to the beach…. Now I laugh at myself because it was just a white-tip reef shark, probably less than a meter long…. And that was my first shark interaction ever.

What message would you leave for those scared of sharks?

It is a natural fear, we are programmed to fear anything that could represent a threat to our survival. That thread is not always real or justified but at the end of the day, it is an evolutionary irrational response. The only way to overcome this kind of fears, is using rational arguments and making our brain understand what is a dangerous situation and what isn’t. We must always remember sharks are predators, not pets, and we should always keep respect and stay alert when interacting with them, but that does not mean that they are dangerous or willing to bite us. Many people visit the Serengeti and there is little concern regarding lions and cheetahs attacking tourists. That is probably because terrestrial safaris have been running since many years ago, and we already learned and realize that lions are not seeing humans as possible preys to hunt. We just know we can observe the lions and other large terrestrial predators safely although their hunting nature. May be, it will take some years for sharks to achieve that same perception, may years sharks do not have.